Interview by Daniel Mariotti

Photos by Daniel Mariotti and Christian Bell

I’m the production manager at Bollinger Atelier, which means I stick my nose into every department’s business. I’m part of a team of creative psychics that channel ideas, concepts, and emotions from Artist to physical objects. We are the builders of incredible things. We take feelings and abstractions and turn them into reality. We are somewhere between scientists, mystics and alchemists; the glorified overworked underfunded tradesmen that build for the challenge of building from our imaginations.

BA: How did you get to the point you got now? Which I know is a huge history but I think a lot of the artisans now are curious about what is different?

Christian: The objects are changing… I guess there’s two questions there, what it used to be like and how I got here…

BA: What did the objects look like and how have they changed?

Christian: It seemed like then was a lot of western, what we consider western, like Native American motif or cowboys. And we almost never see that anymore, and I don’t know if they are just doing that on their own or that style is just gone? It seems like we’re doing a lot more contemporary type stuff. It also seems like the people making the art were the people who actually physically made the art first and brought it to us. Now with digital, it’s becoming more illustrative. People who are illustrators, they’re good at ideas and good at executing on paper and the computer but don’t know how to make anything. And they’re using digital printing and coming to us with that, skipping the step of constructing it themselves. That’s new.

BA: Do you like the artwork that is happening now?

Christian: Some of it is really cool. Actually, the coolest piece of art that I’ve seen in a while was at my son’s house the other night. Someone took a whale vertebrae, big one, did a mold on it and cast it in aluminum. Dude, it was the most badass thing I’ve seen in a long time. Rarely does stuff come through that I’m jazzed about; maybe I’m jaded. There are some things that I look and I’d think oh cool, but then keep walking right past it. To me, the things that are interesting are the things that you would sit and study. Like the COQ is a really cool piece but on our end. It was cool because he (Tom Sachs) did it first using real objects and then we were able to translate it into bronze. The translation is the interesting part to me because we know how hard it is. I think to the general public they don’t have an idea. Sculpture is the stuff you bump into when you’re looking at paintings. People really don’t spend much time looking at sculpture. You’ve got a bunch of sculptures on Main St. and people just walk right past it. They don’t take the time.

BA: Why do you think that is?

Christian: I think after a while it grows on people to whereas when it’s missing; people tend to miss it more. Kind of like a tree, we walk past it. We love the tree and the green it produces but after a while we walk past. And then once they bulldoze them over you start to realize hey it’s gone. And for whatever reason painting has that stigma of looking at it, people want to study it and read into why or what. But for some reason, there’s not much in sculpture that they want to look into. And the only ones people look at are the ones they are told to; The Thinker. You know, people want to look into that one and figure out what he’s doing and maybe it was just a figure study and he lucked out and it stands the test of time as being an interesting piece.

BA: That seems to be a lot of art, the luck factor.

Christian: Yeah that’s a tough one, especially with sculpture because of the transport costs and all the other costs of it existing. A painting you roll it up and off you go.

BA: That’s a great point; if it doesn’t sell you have to find a place for it in your house.

Christian: Yeah I’m the greatest collector of my own artwork. The stuff’s heavy.

BA: So there was a period where you left for a little bit. Worked at BA as an artisan doing devest and…

Christian: Well I actually moved all the way up to metal. I started in devest, and moved through ceramic shell and ran the pours for a while. And would do metal chasing on the side. We started kicking off big with the sand department. It was a kind of easy transition because the sand molds kind of ended up in the pour area so the pour guy helped with the sand and I basically took over that as well. The one department I am most lacking in is patina.

BA: Is it more consistent that an artist wants a sculpture painted vs. a patina if they are painters or ceramicists?

Christian: No…Because we get into this whole thing that bronze is supposed to be a particular way. But bronze, it’s art, it’s sculpture, you can do whatever you want with it. “Well, it’s not a traditional patina”. That argument just drives me nuts. Because it’s like, what is a traditional patina? If you go down to the Greeks and the Romans, those are the guys that were doing the big bronze sculptures and they painted them! They made them look like real people. It was their advertising, their models; it was their way to do stuff. So when someone says it’s traditional, traditional would be to paint the thing. It’s art, it can be whatever you want. And people get confused about what patina is. “Patina is a chemical application on bronze”, well, no, not necessarily. Patina is an ageing process that is everywhere around us. Patina is on your car, patina is the dots on an old lady’s face. It’s anything that gets on the surface from then till now. And how it affects what it looks like.

I think its people not understanding the process. There isn’t anybody being schooled on bronze. Schools are producing students and exposing them to art but isn’t showing them how to market their art, sell their art, perfect their art, and be profitable with their art. We have a hard time training those kinds of mindsets; the ones that work till it’s done; but it’s like, dude, we’re production. I don’t need you to do that. I need you to do it fast, accurate, and ten more times.

BA: Do you think that’s because the teachers teaching that only have a taste of the school system of thought? They haven’t been part of productions so they don’t know how to teach that, so they lean heavily into theory?

Christian: Yeah I would say so. I mean it’s their only exposure. But learning how to pay the bills and how does theory keep 10 other employees working?

BA: So, anyway, in the beginning you were here and then left for Kodiak? Why?

Christian: It was getting too much. I needed a break. We were working at a heavy pace. I mean the job is hard. It’s hot, it’s heavy, it’s out to kill ya, and it’s very stressful. We were building up to do bigger and monstrous things and the heat. I was predominantly the pour guy and working in sand for like 2 years and turning out some huge, huge things. I just needed a change of pace. I went back to bartending because I used to do that in the past. And an opportunity came up to go see Kodiak and I figured that it was an opportunity that if I didn’t do it, I would’ve kicked myself to the end of days for not trying it. It was a place I’ve never seen before. I sold everything and reduced my life to 2000 lbs. Did it for four years and then I was like yeah I’m done.

BA: Was that a similar moment to needing to reset again?

Christian: Over there it was more of the isolation of it. It was definitely a beautiful place but is out in the middle of nothing. It has modern conveniences so people can fool themselves, but you’re on an island 250 miles in the Bering Sea. You know. And when the storms come in and power goes out, there’s no one there to rescue you. Everything comes in by boat or plane. And if they stop running the city stops being alive, and that was a little weird. To me it was missing family and friends, it was too far. I saw it, you know. And I miss the daylight, you know. It was also, if I stay, this is all you’re going to do, because there is nothing else. You either fish, or you’re local. Working in the rain and working in the dark and working the cold it’s just like… I guess it’s the same here right, “oh you gave up working in the cold to working in 120 degree heat”. Eh, I dunno, this seems better.

BA: So why did you come back to Bollinger?

Christian: It kind of just happened. John, my brother, and I were working with Taliesin quite a bit. And I was just odd jobbing it out because there’s enough molds to be made among local artists doing little things. I had talked to Tom and Tom said, “Hey we’re kind of ramping up and could use a hand, why don’t you come part time and you know, come in work when you want, etc.” And then I took the hook line and sinker and yeah, now I can’t leave hahah. Managing people is a trick. I don’t mind doing it, I prefer doing the work for sure, the hands on. It was a hard transition for me, from the guy doing the things, to letting others do it. It’s hard for me not to just push that person out of the way and do it myself. They’re not learning anything if I do the work for them. So I have to let people struggle. And it’s hard because we still have that deadline and bid times to meet.

BA: What got you into sculpture?

Christian: I guess I fell into foundry. Before I started working at Arizona Bronze I didn’t even know foundry existed. Which is funny because my brother John was doing that? I just never considered it as a career and job, though I went to school in the arts. So I just kind of fell into it, just looking for something different to do. And John at that time was like we’ve got a position, it’s gonna suck, it’s in the pit. But what difference does that make? It was consistent. I was looking for that. And then from that because I had mechanical skills, I had electrical skills, I had plumbing skills, it just seemed like a good fit, because anytime something was broken they were like, “Hey Christian, can you fix that?”, so I made myself useful in all departments and just kind of worked out that way, stuck around. It’s like for what we do, even walking through the door, the pneumatics are down, from the air hoses to the jack hammer, to the welder, and we’re constantly needing to rewire something. And so we are constantly improvising and figuring out ways to do things effectively. What’s most challenging is coming up with the right tools and techniques to duplicate the Artist original intent or idea into bronze. There is almost never a specific tool that will do the job right out of the box for bronze. Some type of modifications must be met, either by physically changing the tool or using it in a way that was not intended by the manufacturer. Once you figure out which tool is to be used, then it’s HOW is the tool going to be used. A hard touch or soft, over winding the tool or slowing it down. Rotary motion, reciprocating, oscillating, and linear are all methods that can be applied. The tough part is knowing which to go to first as not to cause more damage than good.

It’s cool. It’s fun to see. And when it works well, you can take a step back. And for Mayo, where you here for Mayo?

BA: Yeah, that was one of the first ones I saw when I started.

Christian: Yeah, when we were doing Mayo and she (Glenna Goodacre) came in, and she was looking at it and was like, I think you did a really good job, you chased it out so nice, where did you put it together?

I’m like; “I’m not showing you that.” If you can’t find it, why would I show you? It means we did a really good job. I see it, because I see my flaws. But it’s one of those things; if I point it out you’ll never un-see it. And right now you’re totally good with it.

BA: Like a magician who reveals his secrets and wonders why he can’t get any gigs booked.

Christian: Oddly specific but yes, exactly. There’s a show, Abstract, on Netflix. It’s a 35 min. blob and it’s all on creative thinkers. It’s awesome. This graphic design person is talking about interactions between artists and designers. Someone wants you to do something and you’ve done it for them. When they come in they are going to be up here, really high. “Oh my gosh what a great thing what a great job you’ve done”, and then they’re going to talk down, “oh what about this?” And you’re going to drop off. Every time they bring up something else, you’ll go back up, but you’ll never hit that same high. And the next time they talk low, it’s lower. And you want to catch them when they start to come up the second time and end the conversation there because it’ll just keep hitting lower and lower. Happens all the time. Whether it’s a mold check, wax check, or metal check. That to me was an epiphany.

BA: That’s funny too because a lot of the times we replicate something and the client picks out things that were wrong in the original. And they ask well why did this happen, and it’s like, well, that’s you. You sculpted it that way.

Christian: Yeah, and most people wouldn’t notice it. Any flaw that’s there, most people would assume that it’s supposed to be that way. And it’s almost that they put more weight in the half ass work. People love that, they relate to it. They’re thinking if I sculpted, that’s what it would look like. Except when they see Studio EIS, people look at that and think it’s a product. They may say oh that’s incredible but they can’t relate to it because they have no idea of how to get there. They relate to the simple things much better. When you give them something they’ve never read before, they don’t know how to relate to it. And so you’re opening up a book where it’s a foreign visual language. And they are like uh what does it say? I don’t know how to navigate this. Little kids come up to my work and love it because they’re pure imagination. They look at it and are like, look at it, it’s cool. Adults come to it and say, I don’t get it. Do you need to know that I’m just interested in trilobites that come from the ocean and it’s just a nice simple form that feels good in my hands?

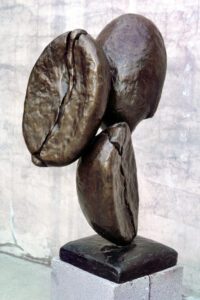

When we did the Pat Tillmans, and his brother came in. He singled out my coffee beans. He’s like, “I never knew that these kinds of people existed. That they could build these things. Pat new. Pat used to go and sit in a coffee shop and loved to talk to these guys”. And he goes, “and I saw Christian’s coffee beans and that spoke to me, because that was what Pat was about. And not so much that I like the coffee beans but that it reminds me of my brother”. It’s cool; I just made them because without coffee there is no art. But for him it wasn’t about the coffee, it was about him relating to his brother and how he saw his brother relating to people. “At 3 o’clock in the morning Pat would be down at the coffee shop talking to whoever he could talk to, to get information and stories out of people because he loved interacting with people”. And he’s like at some point, he thought Pat would open up his own coffee shop. It’s crazy how a simple image can stir so much in people. But I guess that’s what’s cool about art.

BA: Any trade secrets that could help newcomers in sculpture?

Christian: To me it’s, don’t be afraid to open the book and write it down. If you close the book before you write words, it never exists. And people don’t want to listen to their internal voice and will shut it off before it even happens and you need to follow that voice. What ends up happening, they take criticism too wholeheartedly and they stop what they’re doing, closing the book before they have enough of it to have people understand what it’s about. If you’ve got something you’ve got to say, and to me art is speaking through different mediums, then do it.

BA: What’s the hardest process you had to learn?

Christian: Patience. I’m a very impatient person. Being that I’m working on other people’s work, it’s taught me to create what their vision is, not mine. And so I’m constantly forced to add tools to my toolbox that I wouldn’t normally put in there myself. Being able to slow down, critically look at what I’m working on and try not to fight it. Because when you skip steps, trying to get there faster, you’re going to go back and do it all again. So patience would be the biggest thing.

BA: What’s the most rewarding?

Christian: The smell of wax. Because wax equates done.

BA: What’s one thing you want people to know about you?

Christian: That I’ve made it this far? There’s a quote going way back to college, my sophomore year and I was bartending, there was this server. And he said, “You know what, you’re like the nicest guy from hell you’ll ever meet”. And I looked at him and he was like, “dude you’re just friggin’ weird. But you’re just so nice”. And that just stuck with me.

BA: What does it take to “make it” as an artist?

Christian: “Making it” as an artist is about each artists own perspective. One artist’s successes could be seen as a sell out to another. There are artists who, no matter how much they produce or sell, see themselves as failures and struggle with their creations; only seeing the flaws.

I know and work with many “artists” whose works and talents have graced the greatest museums and galleries of the world. They’ve been on display, public and private, in cities like New York, London, Paris, Berlin, Dubai, Tokyo, Beijing, and not a single one of them have their names associated with the work they have done. Yet each one of them loves what they do. They have pride in the skills they possess with the tools they wield. They take great satisfaction in knowing that the objects they’ve created inspire others across the globe. Anonymous or not, that’s making it in my book.

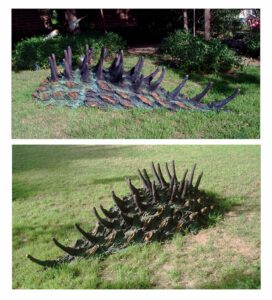

Selection of Christian’s bronze work: