Interview by Daniel Mariotti

Photos by Daniel Mariotti and Taun Olson

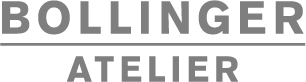

“THE THING THAT DROVE MY SOUL WAS A NEED TO EXPRESS MYSELF IN SOMETHING THAT LASTED.” -Taun Olson

As we meet with Taun Olsen today I am reflecting back on the years he has worked with Bollinger Atelier; Taun was an instant friend of the Atelier when our founder, Tom Bollinger, learned that Taun originated from North Dakota, like Tom, a native of the midwest and therefore arriving with instant credibility!

As clique as this may be, he is incredibly nice (North Dakota) and a joy to work with as a client. We have always found his work to be conceptually interesting but until today had not learned the details of his story and the inspiration for his work:

BA: What was one of the first sculptures you did?

Taun: I saw a sculpture in Bern Switzerland of Einstein and I thought, “I could do at least as well” – so I sculpted Einstein.

BA: Why did the arts pull you? What about it makes you continue creating?

Taun: I was an engineer for years before becoming an artist. I found that everything in software is temporary and good sculpture is forever. Sculpture can last for thousands of years. It’s generational. The thing that drove my soul was a need to express myself in something that lasted. So I had to create sculpture.

BA: Are you a perfectionist?

Taun: Unfortunately, I probably am.

BA: I asked that question because there is always a moment that you keep going on a sculpture and then wonder where/when do I stop. How do you recognize those moments to stop and step away?

Taun: That’s interesting because right before I came in yesterday to drop off that piece, I changed something. I had this 007 girl on her back with a gun and she was wearing a tux and it just looked too cartoonish for me, and I took it off at the last minute. It’s almost like some ghost or spirit is guiding you. Because those decisions can make or break a sculpture in the last moment, but you almost always have to go with your gut.

BA: Describe your challenges as an artist.

Taun: My biggest challenge was being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease 10 years ago. I went through some dark times. Our doctors have known about this disease for over 200 years – but no one could figure out how to stop the progression, halt, or cure it. I spent every week checking the latest studies for something that might be a cure. I tried everything from stem cells to coconut oil. Nothing worked. And it is progressive; so eventually it took away my ability to type, write, and even sculpt. Also, my mother had Parkinson’s and I watched it consume her and destroy her soul. So I knew it was coming for me too. Then, about 16 months ago, I found a novel treatment that required brain surgery and chest surgery called Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS). I decided that it was my best bet and last resort because I would be in a wheelchair soon. So I went under the knife and had a brain aneurism. But I was able to overcome that and everything else over time and now I am 100% normal for the first time in 10 years. Most people don’t even realize that I had Parkinson’s. And I am full of gratitude that I am able to sculpt once again. I just feel bad for all the people it hasn’t worked out for. I don’t know why but I’m the only one so far. I went up and spent almost half of January in Vegas working for Abbott labs, which were the ones that installed the device in me. I have a battery right here [pointing at chest] and then I have a wire that comes up behind my ear and two implants in my head that have sensors that go into my skull. That’s where the leads go and the sensors are just a small pulse that is sent out every couple seconds, and that pulse has gotten rid of 43 symptoms and all of my medications. And they can’t tell me anyone else that has had the results I’ve had. There have been hundreds of thousands that have been through this. Some have been improved but not to the extent that I have. And I keep asking them, “come on there’s got to be someone” and they say no.

BA: How does your engineering background influence your art practice?

Taun: My art has 4 dimensions – 3D + the art of historical expression in each piece. I incorporate hidden objects in my sculptures that hold another dimension of the art. These hidden objects are found in the hair, clothing, etc. of the sculpture and formulate a story that gives extra meaning to the piece.

BA: Was creativity and art a part of your life as a kid?

Taun: It really wasn’t. I just grew up in a rural area, I didn’t know… no one in my family was an artist and there’s no art background, no art in school, nothing. Then I went to college (Bismarck State College) and I took commercial art and was halfway through it and my instructor said, “There’s this computer class and you have to sign up for it”. And at that time, TIME magazine had kindergarten kids that were all taking computer classes with Apple computers and my instructor said: “This is the future, you have to take it.” So I went over to sign up for the class and it was full. And I went back and told him and he went and gave me his spot. And I finished my commercial art degree and then started computer science when I transferred to North Dakota State and got my Masters in computer science there. So when I moved here I started taking courses at the Scottsdale Artist School. The first class I took was from Bruno Lucchesi. And I don’t think I was supposed to be in that class because when I called up to do my deposit, they said to me: “We know who you are.” And I said, “What? How could you know who I am?” And as I was thinking to myself they said, “Oh we’re so pleased you are taking the course.” They had me confused for someone else; I don’t know who that was. Because I never had any background in art or anything and I took the class and it was all professional sculptors who were taking the class. It was intense. People were leaving crying because they couldn’t keep up with Bruno. That was my introduction to sculpture! But I managed to get through the class.

BA: Was he tough?

Taun: He didn’t mess around.

BA: Did you know any of the other sculptors there?

Taun: No, I didn’t know anyone there, I just signed up for the class because it was interesting. I was working as an engineer full time still and was taking classes every semester. I then became friends with Philippe Faraut. I think he’s one of the top 5 living sculptors in the world.

I took a class from Philippe, and when I took the class I was just a beginning sculptor and everybody was asking him out to dinner and he was like “No, nah, I don’t wanna go”. And I thought I sure the hell am not going to ask him because I just heard him turn down several people. And so I didn’t even try and at the end of the day as I was putting my stuff away, he goes “Hey you wanna grab a margarita?” and I go “uh, …yeah?” And we just sat and b.s.-ed the whole time and we did that every day after class. And it just worked out and we became friends and then he saw this picture of the studio I was making and he said, “I’m going to come to teach at your studio.” And I thought he was joking. So I just blew it off and two hours later he calls me and says, “How come you never replied to my email? I wanna come out.” And I go “Whattttt?” And so for ten years, he came to my studio once or twice a year to teach a class and we would sell out the class in 24 hours. So it turned out really well, I mean it was like having Eddie Van Halen teach you how to play the guitar.

BA: And go out for margaritas. How many people were in the class?

Taun: Usually there were about 20-24.

BA: You mention sculpture being more permanent than computer software which I find interesting because it seems that art is being moved and explored into the more techy field. I’m wondering what your thoughts are about that cultural and artistic shift?

Taun: Well here’s the thing, sculpture can last 10,000 years you know, and it can go through house fires; any other medium, something can happen to it and it’s going to be gone. Forever. But that doesn’t really happen with sculpture. It’s almost as if you have children, everyone lives on through the next phase, and if you have classical enough work that can transcend time; then you’ve really got something. I see a lot of modern art, I went to Art Basil. God, it was awful. I wanted my money back. It wasn’t my thing. Then they put a banana up on the wall with duct tape and sold it for $120,000 and it was like, come on. It’s just like, people are trying to see how much money they can spend in a stupid way and impress their friends by doing so. And to me, that’s just ridiculous. You know, there are people that could use that $120,000. Give it to charity instead of a banana.

BA: I think also it stems from the Duchamp idea, where the art is the theory and how do you portray this theory? Through absurdism, I think. There’s a whole bracket of people that think about art and don’t necessarily focus on the crafting of it, and that’s how they express it. Do you think that sculpture needs to evolve to survive where it stands in the art world? For instance, I have a photo background and historically it constantly is being put as science and not art and constantly playing second fiddle to the 2d art world. However photographers have developed techniques to show it’s uniqueness in the form of alternate processes, do you see that happening with sculpture or does it already hold its weight in modern society?

Taun: The thing with sculpture, we’re in a big transition point with it with the era of 3D printers and the development of technology. That’s an art in and of itself because you can do things with it that you couldn’t do otherwise. But there’s something lost. The masters, the classical way of doing things is diminished. People are spray painting on clay on a lifecast. And that’s ok, but it’s different and there’s something lost. You will never be able to get a sculpture that is done by human hands and one done by a machine that looks and feels the same. There’s a lost layer in there. Machines can replicate extremely well and efficiently, but humans can convey emotion through gestures, and you can’t teach or build a code to do that.

BA: That’s a good point. I was reading a Wendell Castle interview who did so many pieces by hand but through the technological revolution and the accessibility of getting let’s say a CNC machine, he could produce his pieces more effectively without causing so much harm to his body. However, he would always do the finishing done by hand to keep that uniqueness and human quality there. So it’s cool to see that he was able to recognize the importance of technology but the beauty and warmness in the human touch.

Going back to honesty in art, I feel that the artists creating work are creating characters of themselves and are selling the image more than the artwork. Do you feel that pressure?

Taun: I think it’s obvious, that to be honest you have to create the work first and will gradually… I don’t know why the process works, but it always does. I’ve had people come to me over the years and say “Oh, I want to be an artist but I don’t know what my niche is, or how I fit into this”, and I’ll say “Well, you’ll find it”. Like love. You don’t know what it is but you can find it and you know what love is. But trying to rush it or get there before it’s done will never happen. You just have to let it evolve.

I think the worst thing that could happen to somebody is them saying, “I will become famous fast”. Because then you’re stuck. And it’s like being typecast as an actor. I’ve always gotta be Johnny Depp and the drunken pirate. I don’t wanna be him, but that’s who everyone thinks I am.

BA: Let’s talk about how the “Running Out of Time” sculpture started and evolved.

Taun: Oh, yeah. That was one of the last pieces I ever did before the surgery. I really didn’t have a title for it. I knew I wanted to have a Dahli-esque type sculpture but also have the guy running. And I worked with Philippe a little bit on it and got some ideas and came back to Phoenix and started working on it. And the idea behind it was that there’s technology and genetics and there are all these things that are working against you. In the piece, there’s this little guy trying to clog up the gears of time. And no matter what he does he can’t stop it. And then it came to me, “You’re just running out of time”. And it was at that moment that I realized it could be the last piece I was going to be able to do. So, I had better make it good.

BA: Besides sculpting, what do you do?

Taun: I also do digital paintings, and I have an engineering degree. With the paintings, I start with my own photographs and then I modify them digitally. I utilize software to paint the image from there. Then I use a lot of different filters to modify it farther and finally, I print them onto a large canvas.

BA: What’s your dream project?

Taun: I have several ideas I have been working on for well over 12 years. One idea is a sculpture of a magician that does a complex magic trick by itself. I just figured out how to do it so I am starting the sculpture now. It should be finished in about 6 months.

BA: Where is your favorite place to be?

Taun: On the move… travelling. I think you can learn a great deal about a culture by immersing yourself in it. That, in turn, helps you appreciate where you come from.

BA: What role does the artist have in society?

Taun: An artist has a responsibility to the public to tell an honest story with their art. It should be both truthful and inspirational. If your art doesn’t tell an honest story – it’s not art. I’ve been all over the world; Russia, China, Thailand, Cambodia, France, Ireland, Japan, Scotland. So, what I used to do when things were rough is that I would go around and look for cures. Like Southeast Asia, one time I was looking for this particular bean that had an abundant amount of dopamine in it. I walked for 10 miles and found it in this one particular stall. I got the guy to give it to me and brought it home and of course, it did nothing, it was just junk. I tried coconut oil and nothing. And all the random things to try to have something help me. Stem cells. You name it. Every time I did a stem cell treatment it was like buying a used car. Nothing ever worked like it was supposed to but it was an experience!

BA: Where does your inspiration come from?

Taun: I know it’s weird but I’ve started sculpting in my mind. My whole life I thought that everybody could see in 3D. I can walk in a building, walk out, put a mental camera in there and see everything in my mind, and thought everyone could do it. But then I started to lose the ability to do that. And I asked some friends about it and they’re like, “I can’t do that.” Now I’ve recently started to get it back since my surgery. But also I sculpt when I can’t sleep in my mind. I’ll think that I’m physically moving the pieces in my mind and pick up different tools and feel the weight of the material resisting on my fingers. So that’s where my inspiration comes from. I think, in general, that we’re a product of our experiences. The more experiences you can have and interpret them in an imaginative way – the more expressive your art can become!

For more information on Taun please check out his website: www.taun.com

and follow him on Instagram for more up to date happenings: www.instagram.com/sculptyou/